Dr. Paul Heins, a member of our Class of 1962, is a Seattle native who entered the School of Dentistry in 1958 after serving in the military. After graduation he took a General Dentistry internship in the Public Health Service in New Orleans. He returned to the UW and completed the Graduate Periodontics program in 1965. He joined the UW faculty that year and began a part-time private practice in Seattle’s Northgate neighborhood. He was Chair of the Periodontal Department in the College of Dentistry at the University of Florida from 1975 until he retired in 1998 as Professor Emeritus. He and his wife, Joyce, then became clinical examiners in clinical trials in the U.S. and Central America. In 2004, they moved back to the Northwest, and now reside in Redmond, Wash.

Dr. Paul Heins, a member of our Class of 1962, is a Seattle native who entered the School of Dentistry in 1958 after serving in the military. After graduation he took a General Dentistry internship in the Public Health Service in New Orleans. He returned to the UW and completed the Graduate Periodontics program in 1965. He joined the UW faculty that year and began a part-time private practice in Seattle’s Northgate neighborhood. He was Chair of the Periodontal Department in the College of Dentistry at the University of Florida from 1975 until he retired in 1998 as Professor Emeritus. He and his wife, Joyce, then became clinical examiners in clinical trials in the U.S. and Central America. In 2004, they moved back to the Northwest, and now reside in Redmond, Wash.

Fifty-five classmates and I sat down to our first class that fall of 1958, an orientation lecture taught by Bert Anderson, the Assistant Dean. After introducing the Dean, Maurice Hickey, he gave us an overview of the next four years of dental school at the University of Washington. In our all-male class most of us were veterans and had the G.I. Bill to help with tuition, instruments and books.

Our studies that first year were a combination of basic and dental sciences where we learned about the human body. Prominent in my memories of that first year was Gross Anatomy. Teams of four of us were assigned a complete human cadaver, and during that first year we dissected, identified and visualized the wonders of the inside of a human body. We did not use rubber gloves, and the scent of formaldehyde on our hands was our constant companion. Of all the body parts, the muscles, tendons, and ligaments of hand and forearm were the most captivating for me. I was stunned by their complexity and design as I imagined the neural pathway from a dentist’s eyes to his brain and the signal down to the muscles of his thumb and fingers holding a hand piece. An incredible construct of engineering.

We had basic science classes in oral anatomy, histology and physiology along with our dental classroom and lab training that was predominately about teeth. Charles Schroeder was a most memorable man. Charlie, as we called him, was a dental technician from Germany. He marched us through a year of drawing teeth and carving of life-sized teeth from stone, all the while demanding perfection. We drew enlarged four-view drawings of each tooth during that year that ended with drawings of an occlusal view of the bones and dentition of a complete skull, both a life-sized maxillary view and a mandibular view. Then it was June and the start of summer vacation and summer jobs. The school year was three quarters in length. In twelve quarters we hoped we’d be dentists.

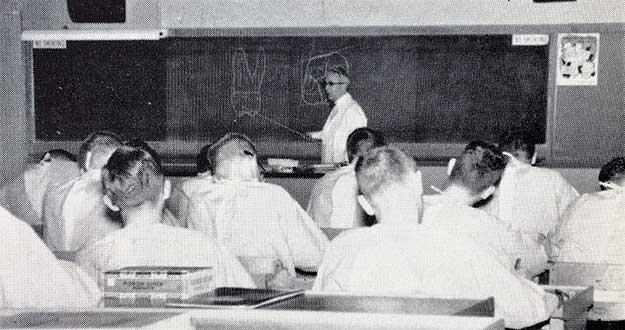

The second year was marked by learning cavity preparation as taught by the gifted artist Lyle Ostlund. He drew beautiful views of cavity preps from various angles on the blackboard. From preparations in stone teeth we progressed to extracted natural teeth that we had begged from dentists in the community who kept extracted teeth in jars of formaldehyde for dental students. Prized were the caries-free teeth extracted for orthodontic reasons. We labored in the second-year lab in our brown lab gowns with Bunsen burners and our electric belt-driven hand pieces. Each of us had a number, assigned in alphabetical order, that went on every assignment and project we handed in. No names, just that number. Seating in the classroom and labs was in that numerical order. As a result we got to know the guys on either side of us very well.

The realization that we might actually become dentists became a reality when we were issued our white “barber” coats. These stiffly starched coats buttoned up the front diagonally from left to right and had our last name embroidered in blue on the collar. With them came 10 charts for the patients who were the beginning of our patient family. We were now juniors and for the first time we would be applying what we had learned during those first two years to the treatment of a human being.

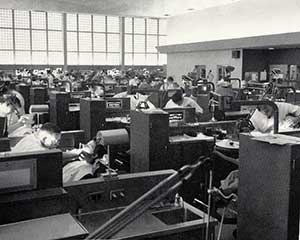

The main dental clinic on the fourth floor was an imposing place, housing more than a hundred dental units, each complete with chair, cabinet, light, and sink. In that massive clinic we performed Operative, Fixed Pros, Perio, and Endo procedures. Instructors from those departments would circulate among the students they were supervising. It was stand-up dentistry, no rubber gloves, cold-sterilization of hand instruments, no face masks … all unthinkable today. Only in Oral or Periodontal Surgery did the budget allow for rubber gloves. Removable Pros, Oral Surgery, Perio/Endo Surgery, and Oral Diagnosis had separate clinics in other locations in the building.

Students arranged their own schedule according to the needs of their patients and their departmental requirements. We submitted a form to Mrs. Soderquist, a cheerful, student-focused clerk who assigned main-clinic units, a week in advance. She sat in front of a massive book that listed every chair and the student assigned to that chair for every half-day in the week.

At the beginning of an appointment I would meet my patient in the waiting room, proceed to my assigned unit, seat and drape the patient, explain the planned procedure and then find an instructor and trail him around as he got successive students started. I would do the procedure, home-care instruction, evaluation of previous treatment and then a quadrant of curettage. When that was done to my satisfaction I’d find the instructor, he’d check it, offer suggestions and possibly a demonstration, and the patient would be dismissed. Then it was time to clean and position the unit.

It was 1960 when I began working in the fourth-floor clinic. The equipment was more than 10 years old by that time and yet it looked like new because the Operative Department administered the clinic and ensured that we took care of it. Each morning a staff member examined each unit. Each chair, each light had to be in a certain position. The stainless steel sinks had to be wiped down with mineral oil and have no water drops in them. A water spot in your clinic sink at 8 a.m. meant the loss of 10 Operative points, the equivalent of a Class II amalgam. So each morning before class, every student checked his unit before the clerk did to be sure the janitor had not bumped the chair or water-control foot pedal during the night. One could look down lines of 30 chairs and see them perfectly aligned, each light and chair exactly in the same position as its neighbor, not unlike a military cemetery with its white crosses.

Practice Management was taught by Assistant Dean Anderson. His course consisted of a series of 10 50-minute lectures on how to run a solo practice. A major assignment was to build a model of a dental office. These models were so good that they could have been part of a course in the School of Architecture. Of course they consumed a huge amount of time to design, assemble the materials, and build.

Four years seemed to pass both slowly and very quickly. I think it was because the faculty was so demanding of perfection. They held us to standards that seemed unattainable. The faculty were determined that those who were graduated were clinicians of the highest quality. The general attitude was “Be able to do it to our standard or you are out.” There seemed to be only two grades, A and E. We were constantly told that our future patients did not want a C dentist. This resulted in an atmosphere among the students that was described in later years by the educational psychologist Robert Guild as WAF: worry, anxiety, and fear. We chafed under the tension and the demands, yet those four years developed and molded us for the better. The rigor and demands of the faculty demonstrated to each of us that we could develop clinical skills far beyond what we thought we were capable of. And now, more than 50 years later, I still feel that it was a privilege to train under men like Gerald Stibbs, an ambidextrous taskmaster who pushed us toward perfection in Operative Dentistry. Class III and Class V gold foil restorations were a significant part of our Operative requirements, and the demanding nature of those procedures developed skills we did not know we had. Gerry Stibbs raised the definition of “attention to detail” to a new level. My close friend and study-buddy through dental school was Herb Hooper. He became a skilled clinician under Gerry’s guidance and won the Gold Foil Award the year we graduated. As for me, when Gerry learned that I wanted to go to Perio school, he said, “Paul, I’m sorry to hear that you are leaving dentistry.”

Members of the faculty were already or would go on to become giants in dentistry. Men like John Ingle, Chair of Perio/Endo, the master of hand instrumentation up a curving root-canal. Alf Ogilvie, a kind scholar-clinician dedicated to sharing his skill with a curette. Ralph Swenson, who, with his gentle smile, taught us to feel the direction a tooth could move during an extraction. Working with the faculty like Ken Morrison in Fixed Pros was rewarding as they developed our crown and bridge skills. Saul Schluger, the charismatic Chair of Perio and Director of the Perio grad program, was a singular individual, a captivating lecturer, a dynamic man unlike anyone else on the faculty. There was Al Moore’s always-present smile. The faculty worked with different styles but the goal was always to produce a superior dentist.

A rich and valuable part of the curriculum were the opportunities to work under the guidance of part-time faculty. These were clinicians who came to the school because they wanted to share their skills with men who aspired to be dentists. They added an invaluable dimension to the fabric of our dental training. Alex Drennan rode a Greyhound bus from Vancouver, B.C. to teach part time. Jack Bell taught me the nuances working in a mouth … gently. The Timberlake brothers came over from their office in the U District and cheerfully helped us through our crown and bridge requirements. There were many others, nameless now, but their contributions to us are not forgotten.

And then there was the support staff. Those folks saw to the day-to-day operations of the School – secretaries, technicians, clerks, and dental assistants. Many of them were like mothers to us, watching out for us, advising, guiding, and helping us get through each stressful day. Folks like Mrs. Gidner, always ready to lend a helping hand. Mrs. Loomis and her leather gold foil mallet. To a person they were pleasant, supportive, and resourceful. They all worked hard to help us.

Graduation approached in June of 1962 as we completed the last of our departmental requirements. We began preparations to take the State Board Exam and at the same time began to make plans for our careers in dentistry. But first we had to pass the State Board. The examination consisted of written and clinical components. For the clinical component we were required to place a two-surface amalgam, a Class III or a Class V gold foil, and a complete, articulated denture set-up. The exam was administered in the main clinic and in the labs we had used for four years and so we were on comfortable grounds, yet tensions were high because the exam was only given annually. A few out-of-state dentists took the exam with us and we gave them every assistance we could in helping them get patients. We wore our “barber” coats with our names covered with tape to preserve the anonymity of the exam. The dentist-examiners were political appointees. Two weeks later we learned that all members of the Class of 1962 had passed the Board.

During the years that followed some events confirmed that I had received a superior, state-of-the-art dental education. The first one was when I took the Washington and California State Boards, then during a general dentistry internship when I observed the work of new graduates from other dental schools. And then 13 years later when I was the Chair of Perio at the University of Florida I realized the quality of the education I had received at Washington. David Granger, the Chair of Operative, asked me to be an examiner in the Operative Section of the Mock Boards. Imagine, a periodontist grading restorative work. That was the reputation the UW has had since the first class began in 1946.

Today’s dental curriculum bears little resemblance to the one I experienced. There is more to learn and more to consider in the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of oral disease. Materials and methods have changed, yet the core goals of the dental curriculum remain the same: the development of the skills necessary to maximize the oral health of the patients we are entrusted to treat.