Dr. Burton H. Goodman, a native of Tacoma, was a product of the Great Depression. As was common in those days, his own dental needs were neglected for financial reasons. It wasn’t until his teenage years, when he recognized a problem in his mouth, that he went to a dentist. Dr. Goodman credits the dentist, whom he calls a role model, with sparking the idea of a career in dentistry. Military service interrupted his studies. He was drafted into the Army toward the end of World War II. As his unit shipped out to the South Pacific, he sat in the contagious ward of the hospital at Fort Lewis, thanks to his bunkmate who had come down with scarlet fever. He remained at Fort Lewis, where he was assigned to work in the dental clinic. With a chuckle, Dr. Goodman proclaims that he fought the end of the war defending Fort Lewis – from dental decay.

Dr. Burton H. Goodman, a native of Tacoma, was a product of the Great Depression. As was common in those days, his own dental needs were neglected for financial reasons. It wasn’t until his teenage years, when he recognized a problem in his mouth, that he went to a dentist. Dr. Goodman credits the dentist, whom he calls a role model, with sparking the idea of a career in dentistry. Military service interrupted his studies. He was drafted into the Army toward the end of World War II. As his unit shipped out to the South Pacific, he sat in the contagious ward of the hospital at Fort Lewis, thanks to his bunkmate who had come down with scarlet fever. He remained at Fort Lewis, where he was assigned to work in the dental clinic. With a chuckle, Dr. Goodman proclaims that he fought the end of the war defending Fort Lewis – from dental decay.

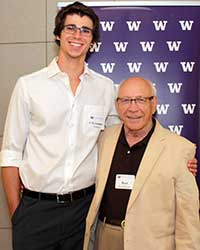

After graduation in 1953, Dr. Goodman returned to Tacoma, where he practiced dentistry his entire career. He was active in the Washington State Dental Association throughout his career and was instrumental in the founding of the Washington Dental Service (WDS, now Delta Dental of Washington), the nationwide umbrella, Delta Dental Plans Association (Chicago), and the WDS Foundation, each of which he served as president. The Foundation recognized his accomplishments by establishing the Dr. Burton H. Goodman Presidential Scholarship, a four-year award to an incoming UW dental student that aims to expand diversity in our School. Here he recalls his memories of dental school.

I was one of the lucky 75 students enrolled in our class. It was 1949, only four years after World War II, and colleges were loaded with aspiring students whose educational expenses were financed by the GI Bill – in other words, a government “gimme.” Consequently, qualified applicants were plentiful and those of us who survived the selection process felt honored indeed. Seventy-five were picked out of an applicant pool of some 700.

We found ourselves stepping into an entirely new building and atmosphere. The bricks and mortar were known as the “Platinum Palace” and kept quite sacrosanct – that is, never leave a scratch, smudge, litter, trash, or anything to deface it or otherwise wear it out. The class size – a fixed number – attended classes all together, every day, five days a week. Quite a departure from upper campus, where the norm was a different mix in every class, with locations spread all over the campus. This led to a rather unique solidarity and almost a feeling of brotherhood between classmates with many such continuing throughout our lifetimes.

The whole new medical and dental school was founded only two years earlier. The two classes ahead of us held classes mostly in Bagley Hall (on upper campus) and transferred for their third year into the new building – which had new, modern dental clinic facilities – so that we were now a three-year school all together in one facility. The entering class after us completed the four-year cycle and the curriculum [was] completed.

The atmosphere in this new school has been described as rigid, structured, disciplined, and perfection-oriented. The Restorative Department dominated the scene, followed by Crown and Bridge and Removable Prosthetics. Periodontia was in its infancy and pretty much defined by “cleanings,” scale and curettage, and surgery – mostly gingivectomies – with a few attempts at bone grafts. Oral Surgery was handicapped by lack of patients to provide other than simple extraction experience and ridge preparation for dentures, which were much more common in those days. Endodontics was pretty much limited to anterior one-rooted teeth, while most pulp exposures on posteriors resulted in automatic extraction.

It was a different era in dentistry. The penultimate dental restoration was considered to be the gold foil malleted in small pellets into the precisely prepared cavity and finished to perfection. Silver amalgams and tooth-colored silicate restorations (they dissolved in saliva over time) were the other ends of the spectrum. Dental Materials instruction was strong. Oral Medicine instruction was virtually nonexistent, and medical management instruction was thin, as were resuscitation and office emergency procedures.

Restorative dentistry was the order of the day. The teaching faculty was dominated by qualified and excellent dentists largely imported from Canada. It was said at the time that they could be hired at a lesser rate of pay than their American counterparts. Of course they were supplemented by a cadre of highly qualified practitioners from our local area. In retrospect, their teaching methods are more reminiscent of the image of Olde English cane-carrying schoolmasters (hey, they never had any canes or beat anybody) than the culture we students were more used to. Excellence was a demand, not a choice. Strict discipline was the order of the day. Many graduates left feeling traumatized and some even bitter. But not everybody; quite happily, I felt different – and I know I was not alone. I liked and appreciated my teachers, especially given the fine direction and instruction urging perfectionism I received. My favorite instructor was Ian Hamilton. Admittedly, I got along well but also [was] fully aware that others felt differently. I seem to recall a class revolt in the class behind us but not the substance or details. Unfortunately, I am aware that some bitterness exists to this day and not limited to any one class.

Lastly, it’s fascinating to reflect on the protocols of those days past. It’s obvious that dentistry has come a long way. After all, it’s been 64 years since graduation. In the school clinic we operated standing up beside the chair, used the old slow-speed hand pieces with pulley-operated drills, sterilized our instruments in cold well solutions, didn’t use gloves or masks, reached in and out of cabinet drawers for instruments and supplies and probably other protocol liberties. Impression materials were something else again.

I’m proud to be a member of the Class of 1953 – we really had a class of winners. We all arrived scared stiff that we wouldn’t make the grade, but we did and became lifelong friends as a result. And I’m proud to be a graduate of a school that has always been a leader, a state-of-the-art pioneer and even more proud of the progress that the institution and the profession have achieved over the years to bring the art and science of dentistry to the prestigious pinnacle it enjoys today. Kudos to all who have helped make it so.